Notes From the Archive: The Liverpool Workhouse Experience

This article describes an incident in 1886, in which a group of eleven migrants from what is now Lebanon were rejected at US immigration and forced to return to Europe. I first read about this incident in Strangers in the West, Linda Jacobs’s comprehensive account of the origins and development of the Arab-American community in Lower Manhattan in the late nineteenth century. In this context, it was a bracing example of what could – and did – go wrong for many would-be migrants. The bare outlines of the story presented there on the basis of contemporary US press coverage prompted me to travel to Liverpool and London to delve into the various archives to find out more, if I could, about the frustrated travellers. During this investigation, it emerged that I was not the first researcher whose curiosity was piqued by this incident. As will be seen, the French scholar of international migration, Dr Céline Regnard, has explored the archives at Rouen and discovered compelling evidence of the eleven men’s identity and home communities.

The case of the Liverpool Eleven highlights the risks of making the journey from the Middle East to the New World, which could be expensive, physically uncomfortable time-consuming and not guaranteed to succeed. The critical moment came when the aspiring immigrant came face-to-face with state or federal immigration commissioners at New York’s migrant processing facilities: first at Castle Garden, then the short-lived Barge Office, and finally Ellis Island.[1] The grounds for rejection were many and various: poverty, insanity, sickness, polygamy, or other 'disallowing criteria' designed to deny entry to undesirables.[2] By 1903, the health guidelines had evolved into a forensically detailed breakdown of 'dangerous contagious diseases', including trachoma and tuberculosis, and 'loathsome diseases', including syphilis and leprosy.[3]

‘Immigrants landing at Castle Garden’, Harper’s Weekly, 29 May 1880, p. 341 Public domain

In most years, a small minority of Lebanese migrants were turned away in this manner. In 1897, for example, just seventy-four individuals out of a total of 4,732 would-be immigrants from 'Turkey in Asia (Arabia and Syria)' were 'debarred and returned' on the grounds of being paupers who were 'liable to become a public charge' to taxpayers, i.e. 1.5 percent.[4] Contemporary records indicate that few took advantage of the right to appeal their rejection – if they were even told that the option was available to them.[5] Nor could migrants from the mutasarrifate of Mount Lebanon count on protection or even representation from the Ottoman consul in New York.[6] At the insistence of the US authorities, it was incumbent upon the transatlantic steamship companies to provide return passage for those refused entry, usually to the European migration hubs of Marseille, Le Havre, Southampton, and Liverpool.[7] There the migrants were left with diminished options, usually dependant on finances. They could try for the US again; they could switch destinations to, for example, Brazil or Australia; they could remain in Europe; or they could return home to the ports of Beirut or Tripoli with nothing to show for either financial outlay or wasted time.

In the spring of 1886, a group of eleven Lebanese men, described at the time as 'natives of the mountain provinces of Syria', were turned away by the inspectors at Castle Garden and forcibly returned to England, where they attracted considerable press attention.[8] Extraordinarily – indeed, as far as we know, uniquely – they were confined for the next five months in Liverpool’s Brownlow Hill Workhouse, among more than two thousand of the city’s most impoverished citizens.

The Brownlow Hill Workhouse in Liverpool © John Mills Photography Ltd., D895/7, by courtesy of the University of Liverpool Library

Their outward journey had been conventional enough: traveling during late 1885 – separately or together is unrecorded – from their homes in the Levant region via Tripoli, Egypt (likely Alexandria), Marseille and Le Havre to Liverpool. They left Liverpool on their final outward voyage on New Year’s Eve aboard the SS Britannic, one of a White Star Line fleet that made the transatlantic crossing once a week in each direction and, for a time, holder of the Blue Riband for the fastest crossing.[9] The Britannic, under the command of Captain Hamilton Perry, arrived in New York at noon on 10 January 1886.[10] The ship’s manifest lists 222 passengers, 50 of them US citizens. The remaining 172 are identified, for immigration purposes, as 'aliens' and represent a fascinating microcosm of European and Middle Eastern migration to the US in this period.

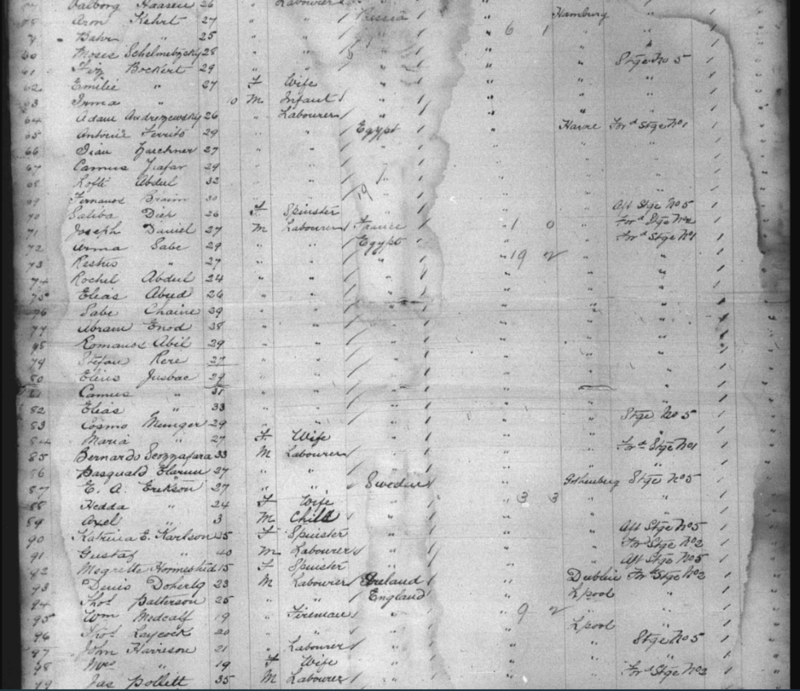

The 172 non-Americans are described in the manifest as follows: 87 English; 26 Irish; 21 'Egyptians'; 8 Swedes; 8 Norwegians; 7 Russians; 6 Germans; 4 'Scotch'; 3 French; and 2 Canadians. The listing of nineteen men and two women as 'Egyptians' illustrates one of the difficulties in researching such itineraries. When Arab names were transcribed by European or American ship’s officers or immigration officials, they were frequently rendered unrecognisable. Manifests, however, were usually more accurate when it came to a traveler’s country of origin: in the case of Mount Lebanon, it was usually given as Syria, Turkey, or Beirut. In this case, however, they were described as 'Egyptian' simply because their maritime journeys had begun, for the purposes of European shipping agents, in Egypt, i.e. at Alexandria (or possibly Port Said). It is possible that none were Egyptian and it is certain that not all were even Ottoman nationals.

Passenger manifest containing the names of twenty-one nationals about the SS Britannic whose maritime journeys had begun in Egypt © Ellis Island Foundation

They ranged in age from 24 to 38. Each male passenger was described as a 'Labourer'. The names of several, including Jean Zarchner, Bernardo Scozzafara, and Cosmo and Maria Munger suggest that they were not Lebanese.[11] Three young men of similar age, their names transcribed as 'Jusbae', may have been brothers or cousins. Ten of those twenty-one individuals, couples, or family groups whose long sea journeys had begun in Egypt, including the two women, were presumably allowed into the United States. At this stage – because deportation records before 1890 have not survived and no notes in respect of detention or deportation were added to the handwritten manifest – we can only reduce the number of possible identities for the eleven men who were to spend fewer than seventy-two hours on shore in New York by removing the names of the two women and those evidently of European extraction. This unsatisfactory process of deduction leaves us with fifteen possible names, which may or may not be accurate representations of the eleven Lebanese identities.

The Britannic sailed from New York on 14 January 1886 at 1.30 p.m., carrying 145 passengers back, among them the rejected immigrants.[12] After their second transatlantic crossing in as many weeks, the men returned to Liverpool on Saturday 23 January 1886.[13] Before the day was out, they were taken from the port, through the centre of the city, and up to the parish workhouse at Brownlow Hill. The workhouse was a destination of last resort for the city’s unemployed, homeless, and destitute. It had expanded, along with the growth of the city itself, from its opening in 1772 to accommodate as many as 2,600 people. The dormitories, segregated by gender, were spartan and the workload arduous: twelve hours a day spent weaving. The workhouse diet was carefully calibrated according to age and fitness: on a Wednesday, for example, an able-bodied inmate would receive '1½ pints Porridge, ¾ pint Buttermilk' for breakfast, '6 ozs. Bread, 1 pint Cocoa' for dinner and '1½ pints Gruel, 6 ozs. Bread' for supper.[14] The Brownlow Hill Admission Register for the day of the migrants’ arrival features eleven anonymous entries, individually numbered from 2680 to 2690 but collectively described as 'Arab Men' in the Name column, as 'Unknown' in the Of What Religious Persuasion column and tagged en bloc as 'From the White Star Line to be paid for'.[15]

The White Star Line's SS Britannic, which carried thousands of Lebanese migrants from Liverpool to New York. Source: Library of Congress det.4a15884 © Creative Commons

This first visit to the Liverpool Workhouse was brief. After a three-day wait for a suitable sailing, they were sent by sea on 26 January 1886 back to Le Havre, where the British authorities assumed they would be processed and sent on their way south via Marseille to Egypt. Instead, they were subjected to five weeks of bureaucratic limbo and physical detention in Le Havre. This is where Dr Regnard’s research in the Rouen archives proves invaluable. On 28 January, the eleven Syrians, who had spread out through the town to beg for alms, were detained by the Le Havre police. With the Ottoman consul in the port city refusing to take charge of them, 'alleging that they do not have papers', local sub-prefecture officials were forced to beg the interior ministry in Paris to take up the case with the Ottoman ambassador in the capital.[16] According to a longer report four days later, the migrants had not just been begging but were 'covered in lice' when they were found: local officials 'had each of them take a bath and had their items of clothing disinfected.'[17] They were then confined to a transit barracks, where they were quizzed by an Arabic-speaking local resident, Emmanuel Rosenzweig. This inquiry provides us with a detailed list of their names, ages, marital status, and points of origin – the latter all given, generically, in Ottoman Syria:

- Chane Seben, âgé de 27 ans, célibataire [single] né à Birchalo,[18] Syrie (Turquie);

- Talous, Héries, âgé de 21 ans, né à Jubil,[19] domicilié à Birchalo (Syrie), célibataire;

- Boulous, Joseph, âgé de 30 ans, célibataire né à Boulet,[20] domicilié à Birchalo;

- Jesbit, Liès, âgé de 23 ans, célibataire né et domicilié à Birchalo;

- Crat, Ibrahim, âgé de 27 ans, célibataire né et domicilié à Birchalo (Syrie);

- Gesbit, Liès, âgé de 45 ans, veuf [widower] né et domicilié à Birchalo (Syrie);

- About, Liès, âgé de 35 ans, célibataire né et domicilié à Birchalo (Syrie);

- Abdalla, Rochi, âgé de 50 ans, célibataire né à Jubil et domicilié à Birchalo (Syrie);

- Betrous, Seben, âgé de 20 ans, célibataire né à Croblis,[21] et domicilié à Birchalo (Syrie);

- Antonous (Seben), âgé de 23 ans, né et domicilié à Birchalo (Syrie);

- Stephan Riz, âgé de 33 ans, né à Boulet, domicilié à Birchalo (Syrie).[22]

It can immediately be seen that the names as transcribed by officials in Le Havre are, in many cases, impossible to reconcile with the same names as taken down by those who compiled the passenger manifest aboard the SS Britannic – but at least we have eleven credible identities. We might also deduce that this group of mainly single men, all from the same small community in coastal Lebanon, had travelled out to America together, just as they were now incarcerated in France together. While they languished – albeit clean and fed – the French bureaucracy tried to figure out what to do next. By mid-February, 18 days after the arrest, Le Havre sub-prefecture officials were complaining that no reply had been forthcoming from the foreign ministry in respect of its negotiations with the Ottoman embassy and that, with the situation threatening to 'drag on', an impatient city mayor was about to let the Syrians go free.[23]

The response from the interior ministry in Paris was decisive, advising Le Havre that the Ottoman embassy was refusing to repatriate the migrants, and instructing local officials immediately to draw up deportation orders.[24] While the paperwork was being processed, sub-prefecture officials advised Paris that, while there was 'the greatest urgency to expel them', it would be expedient to 'avoid directing them to England … where the local authority would certainly not let them disembark', and instead pursue 'the only practicable route … to Marseille, where they would perhaps find it relatively easy to return to their country of origin.'[25] This advice was ignored. The expulsion orders were signed on 27 February 1886, one document for each named individual:

'Whereas Talous (Hiriès), born in Jubil (Syria), was arrested in Le Havre, on January 28, 1886, in a state of vagrancy; whereas he has no established domicile in France or means of subsistence; [and] considering that the presence of the above-mentioned foreigner on French territory is likely to compromise public security ... Talous (Hiriès) is ordered to leave French territory.'[26]

Again, it took a few days to organize an appropriate vessel but on 5 March 1886 the eleven men were individually informed of their expulsion from France and, at 7.30 the same evening, put on board the British Queen heading back to Liverpool.[27] For several days, French officials held their breaths, expecting their English counterparts to respond in kind – but by mid-March, when the British Queen returned to Le Havre without the Syrians, 'who remained temporarily in an asylum in Liverpool', they began to relax.[28]

Telegram dated 13 March 1886 confirming that the migrants had remained in Liverpool © Archives Départementales de la Seine-Maritime (Rouen), 4M809

In England, by contrast, the case of the eleven returned travelers escalated rapidly. Before it was resolved, it would involve three British government departments, the mayor and head constable in Liverpool, at least one influential Member of Parliament and the Ottoman ambassador to London – not to mention the slow-moving bureaucracies of Istanbul and the Levant. Most immediately, there was consternation in the city that the migrants had been returned.[29] With other official sources silent, only the Admission Register at the Brownlow Hill Workhouse records their return on Friday 12 March 1886 – a full week after their forced embarkation at Le Havre. Unlike his French counterparts, the duty workhouse secretary again did not bother even to attempt the new arrivals’ names. They were individually numbered for the purposes of the ledger – 3798 to 3808 this time – but in the Name column all were entered as 'Arabs', with 'Arabia' entered under Settlement and 'Destitute' under Trade Or Calling.[30] No additional effort went into the workhouse’s Religious Creed Register. This time, entry 3798 was identified as 'Arab No. 1', 3799 as 'Arab No. 2' and so on, while no effort was made to record the frustrated migrants’ faith or faiths – the sole function of an otherwise meticulously kept ledger.[31]

The story was picked up swiftly by the city press, where coverage was generally sympathetic towards the eleven men, now firmly identified as 'the destitute Syrians' by all parties. 'They are intensely anxious to get back to their own country,' noted the Liverpool Daily Post, two weeks after the migrants’ return to the workhouse, 'and they state that if they are landed at Beyrout they can readily make their way back.'[32] The Manchester Guardian, by contrast, appeared to think that the Liverpool eleven had chosen their accommodation: 'This is an example of the way in which our regulations, or the absence of them, enable any person, no matter how destitute he may be, to land in England and at once seek quarters in the nearest workhouse.'[33] When the news reached America the following month, the New York Times relished what appeared to be a case of biter bit:

'Great Britain and Continental countries take no interest in the paupers whom they send here, so long as they gain admission to our workhouses and asylums. In this case the tables are turned, and in Liverpool at least they know something about the burden from abroad that the taxpayers of this State have to bear.'[34]

The British Queen © University of Liverpool Library, D42/PR2/1/36/C1

The church bureaucracy that ran the workhouse, known as the Select Vestry, swung into action as vigorously as the press.[35] On 24 March 1886, the vestry clerk, Henry Hagger, wrote to the Local Government Board in London to relay the view in Liverpool that 'the action of the French authorities … demands explanation', urging that the Foreign Secretary himself should demand that explanation and suggesting that 'the Turkish Government whose subjects they are will move in [sic] their behalf.'[36] The Local Government Board promptly forwarded the letter to the Foreign Office but received a frosty reply ten days later from Thomas Lister, on behalf of the foreign secretary, noting: 'Under the circumstances Lord Rosebery does not think there are any good grounds on which to found a representation [of complaint] to the French Government':

'If the Local Government Board should consider such a course expedient, His Lordship would be prepared to lay the facts before the Turkish Ambassador in London with a view to His Excellency’s obtaining authority for the repatriation of these distressed Turkish subjects, but it does not appear probable that the application would meet with much success, and Lord Rosebery is disposed to think that in the long run the most economical plan would be to ship the destitute Syrians back to their own country at the expense of the city of Liverpool where they now are.'[37]

This brusque response belied the intense activity embarked upon in the last week of March by Foreign Office staff and their counterparts at the Home Office. The Home Office had been contacted by William Waddington, the French ambassador in London, who passed on a request from Paris that the eleven Syrians would not be sent back to Le Havre.[38] Waddington’s letter confirmed the details of the recent episode in Le Havre, including the refusal of the Turkish ambassador in Paris 'to take any steps in the matter', and concluded with a personal request from Prime Minister Charles de Freycinet that 'the Syrians be sent to their own country instead of being landed on French territory.'[39] Before replying, the home secretary, Hugh Childers, commissioned an investigation into the incident by the Liverpool Constabulary Force, which was promptly carried out and forwarded to London by the mayor of Liverpool, David Radcliffe.[40]

The next round of correspondence was again triggered by the workhouse committee, which, having received no reply to its earlier appeal to the Local Government Board by its next meeting on 15 April, approved a follow-up letter, describing the 'pitiable' condition of the migrants who were 'pining to get back to their families, nine of the eleven having wives and children in Syria.'[41] Again, the Local Government Board forwarded the complaint to the Foreign Office; this time, the foreign secretary authorized his permanent under-secretary, Sir Julian Pauncefote, to write to the Ottoman ambassador to London.[42] Ironically, its recipient, Rustem Pasha Mariani, had spent the decade before his appointment in London as governor of the Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate – so he understood exactly the phenomenon of migration represented by the Liverpool Eleven.[43] Pauncefote’s letter summed up the migrants’ case so far and concluded, somewhat wanly: 'I beg accordingly to lay the foregoing statement of facts before Your Excellency with a view to such action as the Turkish Government may desire to take for securing the return of these distressed Ottoman subjects to their native country with as little delay as possible.'[44]

The letter also gives us another clue about the travelers’ origins, describing them as 'nationals of Tripoli'. If this is accurate – and not just an indication of the port from which they left the Levant – it places them outside the jurisdiction of the mutasarrifate of Mount Lebanon and, instead, in that of the separate Syrian sub-governorate of Tripoli (Ṭarāblus al-Shām). In any case, the answer indicated that patience might be required on the part of the British government:

'As the individuals in question belong to the class of emigrants, and not to the category of shipwrecked seafarers or other needy persons whose repatriation is provided for by consular regulations, the Embassy could not take a decision in this regard without referring first to the Sublime Porte. I did not omit, however, to ask the Imperial Ministry whether it would, in this case, make an exception to the established rules, and authorize the return to Syria of the persons indicated.'[45]

Unlike the workhouse staff, the press wanted to hear from the migrants themselves and by mid-April, their voices – albeit mediated – were beginning to be heard for the first time. The mediator in question appears to have been the veteran Ottoman consul-general in Liverpool, Pierre Mussabini, who was a partner in a Greek Liverpool-based shipping company.[46] 'The gentleman acquainted with their language,' reported the Evening Express on 15 April, 'who had on one or two occasions kindly attended and talked with them, had had another interview with them since the last meeting of the committee, and the scene was very affecting. The poor men cried like children, and begged that something might be done to get them to their own homes.'[47]

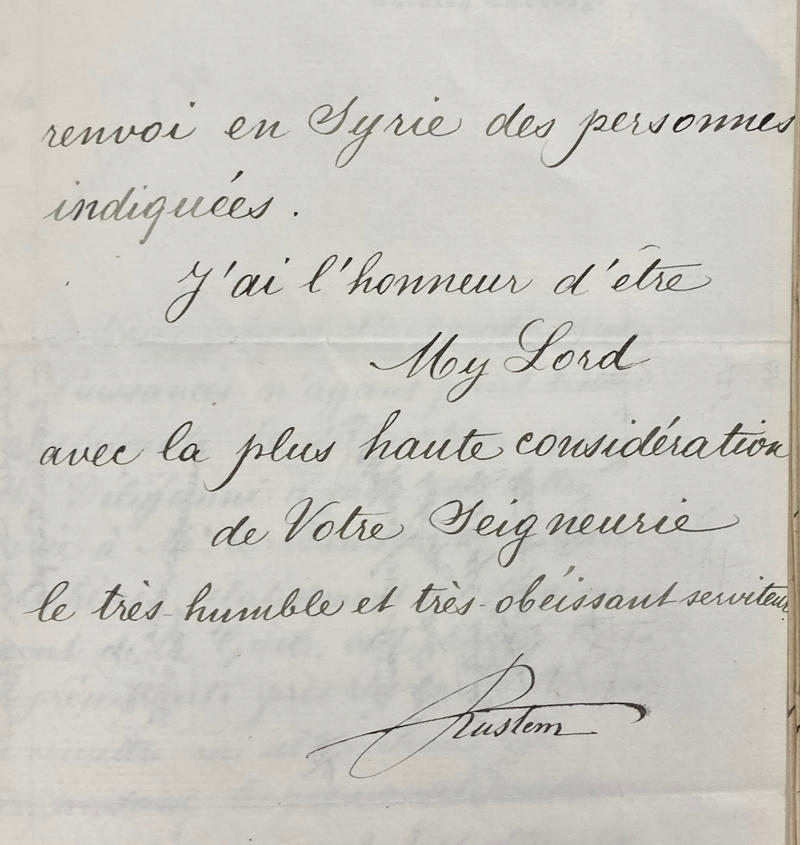

Signature of Rustem Pasha on a letter to Lord Rosebery, 28 April 1886 © The National Archive, Kew, FO 78/3916

Week after week, successive meetings of the workhouse committee were updated on a three-way correspondence developing between the Local Government Board, the Foreign Office and the Ottoman embassy in London, with the additional intervention of William Rathbone, a member of parliament who had previously represented Liverpool and who still maintained an active interest in the welfare of workhouse inmates.[48] The Select Vestry was careful to express its gratitude to the Foreign Office for its interventions, although Henry Hagger expressed surprise that Liverpool was adjudged by Lord Rosebery to be in any way different from Le Havre, inasmuch as the two port cities had the same transit status 'in the ordinary course of emigration traffic'. With admirable prescience, Hagger made an explicit request: 'In the event of the Turkish Ambassador declining to send the men back to Syria, it is desirable that His Excellency be requested to give the necessary authority for their landing at Tripoli or Beyrout should they be sent home by charitable or other agency.'[49] But progress was too slow for the Liverpool Echo, which on 26 April lamented the dawdling treatment of these 'luckless subjects of the Sultan':

'Weeks and months roll by, and the case of the destitute Syrians still remains in the hands of the Circumlocution Office. ‘My Lords’ of red tape and sealing wax are energetically employed in writing despatches and soliciting interviews regarding these unfortunate paupers. Had they fallen into the hands of Red Indians they would have been scalped and put out of [their] misery long ago. The torture of civilisation is of a more tedious and refined character. They are being slowly done to death by mental anxiety, home-sickness, and anguish at the thought of their probably starving wives and children.'[50]

If the deadlock were to be broken, it would only happen as a result of the correspondence between the Foreign Office and the Ottoman ambassador, which continued behind the scenes. On 21 May, James Bryce, the under-secretary of state for foreign affairs, gently chivvied Rustem Pasha for an answer to Rosebery’s earlier letter.[51] In doing so, however, he made an error, suggesting that the vestry would be willing to pay for the eleven return journeys from Liverpool to Beirut: 'I believe that if passports, or some other form of permission for their return, can be issued to them, it is not impossible that the Liverpool authorities may find some means of contributing to the expenses of their passage home.'[52] In his prompt reply three days later, Rustem Pasha apologized for the delay, occasioned by 'the necessity of entering into communication on the matter with the authorities of the province from which these persons emigrated' and noted with appreciation Bryce’s reference to 'the kind disposition of the Liverpool authorities towards these poor people'.[liii] The seed of a future disagreement over payment for passage had thus been sown.

During the summer of 1886, various proposals of employment were put forward to enable the Syrians to escape the workhouse. On 3 June, the entrepreneur William Cross, owner of Cross’s Menagerie on Earle Street, attended a workhouse committee meeting and 'applied to be allowed an interview with the Syrians … stating that he is desirous if possible of finding some employment for them.' The committee agreed, no doubt hoping to have eleven fewer mouths to feed.[54] Nothing appears to have come of the negotiations, although Mr. Cross’s name came up a week later, in the context of a proposal that 'the band of Syrians who are perforce being detained at the Liverpool Workhouse might with advantage be transferred to the Indian Village' at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition then underway in South Kensington in London.[55] The proposal appears to have foundered on 'the uncertainty as to the time of the departure of the Syrians' rather than their capacity to masquerade as Indians.[56]

Coincidentally, there was a similar event underway much closer to home: the International Exhibition of Navigation, Commerce and Industry being held at Liverpool’s Wavertree Botanic Gardens.[57] A correspondent to the Liverpool Daily Post, signed only as 'Translucent', wondered whether the Syrians might not be 'employed in the handicrafts peculiar to their country' and so lifted 'out of a state of enforced pauperism'.[58] Similar sentiments were expressed by J.F.L. Chaig in the Liverpool Mercury:

'The Laplanders have journeyed 3000 miles to add to the splendour of our International. The Ashantees came 3000 miles for the same purpose. The Syrians came 3000 miles for no purpose, and were left without home or the means of procuring food. We have entertained (?) them in Liverpool as paupers. Why not put them to some industry in the Exhibition? Why not make them useful, pay them for their labour, and thus enable them to return to their homes independent as every British subject would wish to feel when he is left destitute in a foreign port?'[59]

While such debates were conducted in the daily papers, the diplomatic dance continued. Absent any reply from Istanbul, Rustem Pasha declined either to issue passports or to transport the eleven men back to Mount Lebanon. Commenting on the 13 May workhouse committee meeting, at which updates from the Foreign Office had been relayed by Rathbone, the Daily Post observed drily: 'The case of the destitute Syrians was again before the Workhouse Committee of the Select Vestry, yesterday, when it appeared that the Turkish Government relied on the argument that by leaving their native country without permission the emigrants had lost all claim to their rights of citizenship. At present, therefore, the Syrians are in the curious position of being literally outcasts from society.'[60]

This was, in fact, an overstatement of the ambassador’s position. He had not declared that the travelers were no longer Ottoman nationals, only that their predicament did not meet the criteria laid down under international agreements for the consular protection and repatriation of, for example, stranded seamen. The eleven men had certainly not contravened the 1869 Ottoman Citizenship Law, which only spoke of citizenship being stripped from 'any Ottoman subject who shall have naturalized himself in a foreign country or who shall have accepted military functions under a foreign government without the authorization of his sovereign.'[61] After all, they had barely seen America, let alone applied for citizenship there. It would not be until August that the ambassador came closer to the position outlined in the Daily Post.

In the meantime, he was chivvied again by Bryce in more forthright language. 'The circumstances of the case,' Bryce concluded a terse note on 5 July, 'make it very desirable that steps should be taken for the repatriation of these distressed persons without further delay.'[62] Rustem responded on 9 July with the news that he had just received authorization from Istanbul to issue passports to the eleven men, and had instructed the new consul-general in Liverpool – another Ottoman Greek Christian, Dimitri Mavrogordato – accordingly.[63] Rosebery took over the correspondence at this point, thanking Rustem in person 'for the steps which you have taken in this matter'.[64] The Local Government Board was advised of this progress on the same day.[65] The Liverpool Echo, however, as yet unaware of the breakthrough, continued to express indignation at the 'nonsense and red tape in the matter':

'A first-class treaty might easily have been negotiated in a quarter the time it has taken to secure the removal of the poor Syrians to their own homes. It has been suggested that the parish should give the men a small sum of money in their pockets and send them on again to America, where they wish to go. But it may well be doubted if the United States authorities would allow their law against pauper immigration to be thus evaded. Besides, these unfortunate Syrians are marked men.'[66]

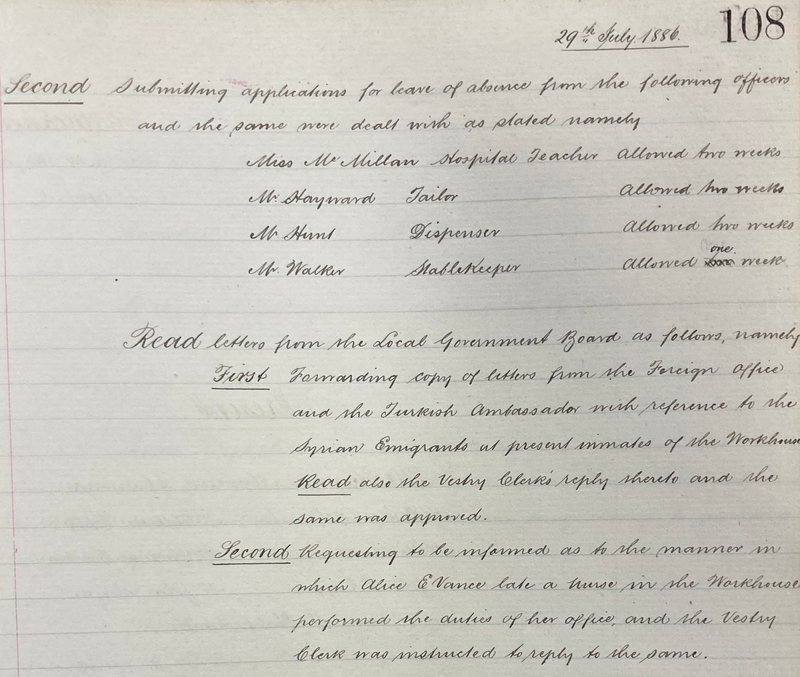

Extract from the Workhouse Committee Minute Book, 29 July 1886 © Liverpool Record Office, 353 SEL/10/12

The next delay in the case had nothing to do with internal Ottoman bureaucracy or haggling over ticket prices. At the end of July, the Gladstone government was thrown out by the British electorate and Lord Rosebery departed from the Foreign Office.[67] But the civil service continued its work and, in the middle of the protracted voting process, the weekly meeting of the workhouse committee on 22 July 1886 was read a letter from the Foreign Office addressed to Rathbone, confirming that 'authority has now been given for the issue of the necessary passports to the Turkish Empire to the Eleven destitute Syrians.'[68] 'The Turkish Government were now prepared to take over the charge of the eleven pauper Syrian emigrants,”'reported the Mercury the following day, inaccurately: 'The passports had already been supplied by the Ottoman Consul in Liverpool, and the Syrians would be sent away by the next steamer.'[69] But there was still the question of payment for the migrants’ tickets home. When Henry Hagger wrote to the Local Government Board on 28 July, he noted:

'The Foreign Office would appear to have given a more liberal interpretation to the Ambassador’s letter of the 9th instant than the language actually employed will warrant. At any rate the Turkish Consul General at this port understands his instructions to mean that he is to limit his interference top the issuing of passports to the persons in question, and that upon no account is he to incur any pecuniary responsibility in connection with their being sent home.'[70]

This message took a few days to reach the Foreign Office as the Local Government Board decided how best to proceed.[71] When they did ask the Foreign Office to make one more approach to the Turkish ambassador, the same note of alarm as was apparent in Hagger’s letter was clear in a brief letter of 4 August 1886 from 'JB', suggesting that James Bryce had remained in post in an interim capacity. Relaying the point about Mavrogordato’s refusal to entertain any thought of paying for eleven tickets to the Levant, Bryce wrote: 'These unfortunate persons are entirely destitute of means, and consequently unable to defray the cost of their passage to Beyrout; and under these circumstances I have the honour to inquire whether I was in error in assuming from the terms of Your Excellency’s note, that your Government would defray the cost of their repatriation.'[72] This belated and somewhat pathetic attempt was made too late: the eleven Lebanese travelers had already left Liverpool by the time the Ottoman ambassador replied.

On 5 August, the vestry clerk at Brownlow Hill, Henry Hagger, informed his colleagues that 'arrangements had now been made for sending the men to Beyroot by a vessel leaving Liverpool upon the sixth instant [6 August 1886].'[73] The Liverpool public who had been following the saga were given the news that same evening.[74] Hagger confirmed their departure in a letter to the Local Government Board on 7 August.[75] The precise route south remains unknown. Officials in Le Havre certainly did not want the Syrians passing through their port again: one telegram urged the foreign ministry in Paris 'to try to obtain from the English Government the repatriation of [the Syrians] without using our territory again', while advising Le Havre port authorities that 'it would be in your interest to give the necessary instructions to oppose their disembarkation.'[76]

It also remains unclear whether the Foreign Office or the Local Government Board offered to help the Select Vestry to foot the bill for eleven tickets on the long return journey via France and Egypt – but it is certain that the Ottoman authorities did not. The workhouse committee’s final meeting on this unique problem heard on 19 August the gloomy confirmation: 'Read further letter from the Local Government Board … from which it appeared that the Turkish Government decline to defray any portion of the cost incurred in sending the men back to their own Country.'[77] This position had been made icily clear in Rustem Pasha’s final letter on the subject, in which he came close to the position attributed to him by the Daily Post back in May, i.e. that by leaving Mount Lebanon without valid documentation the migrants had effectively forfeited any rights pertaining to Ottoman nationality. The letter, addressed to the new Conservative foreign secretary, Sir Stafford Northcote, now the 1st Earl of Iddesleigh, is worth quoting at some length:

'Referring to the correspondence which has been exchanged on the subject of this affair, I see that, on 3 July last, the Consul General of Turkey in Liverpool wrote to me that the Workhouse committee had offered to take upon itself the responsibility for the travel expenses of these individuals from Liverpool to Beirut, provided that he was certain that they would be allowed to disembark at the port of destination, and that to this end, the committee requested the Consul General to issue them with passports. I telegraphed the Sublime Porte to find out if, under these conditions, the return of the emigrants was authorized; and the answer having been affirmative, I informed the Consulate General, inviting him to come to an agreement with the Workhouse authorities and issue the passports, but in the spirit of the proposal made by the committee relating to travel expenses. Owing to an oversight, this circumstance was not explained more clearly in my note addressed to your Lordship’s predecessor on 9 July. The individuals in question had permanently [à titre définitif] abandoned Turkey to settle in the United States. They do not fall into the category of indigents whose repatriation is provided for and authorized by consular regulations. The Ottoman Government, to whose attention I brought the case of these individuals, did not judge that there was reason to deviate from the established rules in their favor, and, while not opposing me in respect of their return, the Sublime Porte did not believe it could impose on their account a sacrifice to which the circumstances in which they left the country gave them no right.'[78]

The eleven Lebanese would-be migrants were denied their dream of a new start in a new country. We cannot know whether they sought to make a permanent home in the US, perhaps sending for their families when they were settled, or were planning to transfer remittances back to Mount Lebanon, or to earn a sufficiently comfortable nest-egg with which to return themselves. In any case, all such options were removed when their evident poverty prompted US immigration officials to deny them landfall. Having received no assistance at all from their putative diplomatic representative in New York, they received only a modicum of support from the consul in Liverpool, experienced the dead hand of Ottoman bureaucracy during the protracted arguments over their return to Mount Lebanon, and had their case to return to the Tripoli nearly sabotaged by their own ambassador in London. At least when they did return to their homeland, they were presumably accorded a little more personal respect than being simply labelled 'Arabs Nos. 1 to 11'. As for the Brownlow Hill Workhouse, the imposing structure was demolished in 1931: the site today is home to the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King – known to irreverent non-Catholic Liverpudlians as 'Paddy’s Wigwam'.

[1] Castle Garden, a well-known entertainment centre, was commandeered in 1855 by New York City and state officials for immigrant processing. More than eight million people passed through the crowded and sometimes chaotic Emigrant Landing Depot before it was closed by the federal government in 1890 and replaced, temporarily, by the nearby Barge Office facility and then, from 1892, by the Ellis Island Immigration Station: Ellis Island Overview and History: https://www.statueofliberty.org/ellis-island/overview-history/ (accessed 4 August 2023). See also Vincent J. Cannato, American Passage: The History of Ellis Island (New York: Harper Collins, 2009). Amy L. Fairchild, Science at the Borders: Immigrant Medical Inspection and the Shaping of the Modern Industrial Labor Force (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 1–4, has written (with support from oral history) of the ‘enormous trepidation’ experienced by immigrants awaiting their health inspection.

[2] Linda Jacobs, Strangers in the West: The Syrian Colony of New York City, 1880–1900 (New York: Kalimah Press, 2015), 34–52. See also Roger Daniels, Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants Since 1882 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004), 3–26. Aristide R. Zolberg, ‘Global Movements, Global Walls: Responses to Migration, 1885–1925’, in Wang Gungwu (ed.), Global History of Migrations (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997), 294–303, discusses health inspections in the context of increasingly restrictive US immigration controls leading up to 1924, i.e. forming part of a ‘global network of barriers that successfully confined most of the world’s population in their countries of birth’. By contrast, Fairchild, Science at the Borders, 5–19, argues that the medical examinations carried out by the US Public Health Service (hereafter PHS) ‘acted as an important inclusionary mechanism ... shaped by an industrial imperative to discipline the laboring force in accordance with industrial expectations.’

[3] Barry Moreno, Encyclopedia of Ellis Island (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004), 64–9.

[4] US Immigration Commission, Annual Report of the Commissioner-General for Immigration to the Secretary of the Treasury for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1897 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897), 14. This is a smaller percentage than the figure for all migrants over a longer period: ‘The PHS inspected more than 25 million arriving immigrants from 1891 to 1930, but it issued only some 700,000 medical certificates signaling disease or defect’, i.e. only 2.8 percent of would-be immigrants were certified but most of those were sent back to their port of origin: Fairchild, Science at the Borders, 4. The category of being 'liable to become a public charge' stemmed from the 1882 Immigration Act: see Roger Daniels, 'Two Cheers for Immigration', in Roger Daniels and Otis L. Graham (eds.), Debating American Immigration, 1882-Present (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001), 8–14. See also Howard Bromberg, “Immigration Act of 1882”, in Encyclopedia of American Immigration (3 vol., Pasadena, CA: Salem Press, 2010), ii, 526–7, available online at https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1492&context=book_chapters.

[5] ‘The immigration officer in charge may refuse to accept an appeal after an alien has been removed from an immigration station for deportation, provided the alien had a reasonable opportunity of appeal before such removal’: Darrell H. Smith and H. Guy Herring, The Bureau of Immigration: Its History, Activities, and Organization (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1924), 83–4.

[6] Xenophon Baltazzi, from a wealthy Greek racehorse-owning family in Smyrna, had served as consul in New York since 1880, following a decade as First Secretary and Chargé d’Affaires at the Ottoman Legation in Washington D.C. His work was varied, embracing US-Ottoman commercial relations, the life of the large (mainly Lebanese) immigrant community and intelligence gathering: Sinan Kuneralp, ‘Ottoman Diplomatic and Consular Personnel in the United States of America, 1867–1917’, in American Turkish Encounters: Politics and Culture, 1830-1989 (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), 100–108.

[7] Cannato, American Passage, 49–54.

[8] Liverpool Daily Post, 26 March 1886, 5.

[9] Shipping and Mercantile Gazette and Lloyd’s List, 1 January 1886, 5, via Microfilm 157, Archives Centre, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool (hereafter MMM). The SS Britannic, built at the Harland & Woolf shipyard in Belfast and owned by the White Star line, set out on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York on 25 June 1874. With a capacity of 1,500 steerage passengers, she carried immigrants to America for nearly thirty years, sailing via Queenstown (now Cobh) on the south coast of Ireland: Richard De Kerbrech, Ships of the White Star Line (Hersham: Ian Allan Publishing, 2009), 25–9, and Paul Louden-Brown, The White Star Line: An Illustrated History 1869-1934 (Liverpool: Titanic Historical Society, 2001), 44. On the fastest crossing (an average of 15.94 knots on its fifteenth (eastward) voyage), see Frank C. Bowen, A Century of Atlantic Travel, 1830-1930 (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1932), 140.

[10] Shipping and Mercantile Gazette and Lloyd’s List, 11 January 1886, 5. See also ‘Captain Hamilton Perry’, GG Archives, https://www.ggarchives.com/OceanTravel/SteamshipCaptains/CaptainHamiltonPerry.html, and ‘S/S Britannic (1), White Star Line’, Norway Heritage, for details of the vessel’s journeys from 1874–1903: http://www.norwayheritage.com/p_ship.asp?sh=brit1.

[11] The names of the twenty-one 'Egyptians', as can best be deciphered from the manifest, were: Antoine Ferrito [almost certainly European], 29; Jian [Jean] Zarchner [almost certainly European], 27; Camus Jiafar, 29; Lofti [Lutfī] Abdul, 32; Fernanos Braim [Ibrāhīm], 30; Saliba Diep [admitted to the US], 26, Spinster; Arma Sabe, 29; Restus Sabe, 27; Rochel Abdul, 24; Elias Abud, 26; Sabe Chaine, 39; Abram Enod, 38; Romanos Abil, 29; Stefan Rere [almost certainly German], 27; Elius Jusbae, 29; Camus Jusbae, 31; Elias Jusbae, 33; Cosmo Munger [almost certainly German and admitted with his wife], 29; Maria Munger [admitted to the US], 27, Wife; Bernardo Scozzafara [certainly Italian], 33; Pasqual Harun, 27: Passenger Search, Ellis Island Foundation: https://tinyurl.com/9y748zye.

[12] Shipping and Mercantile Gazette and Lloyd’s List, 15 January 1886, 5.

[13] Ibid., 25 January 1886, 5.

[14] The National Archives, Kew (henceforth TNA, Kew), MH 12/5999, 40804/86, 'Workhouse Brownlow Hill – Dietary for Healthy Inmates', Parish of Liverpool, 1873, enclosed in Local Government Board (henceforth LGB) correspondence dated 28 April 1886.

[15] Liverpool Record Office (henceforth LRO), microfilm of ‘Admission Register (25 January 1885–25 September 1886, A-K)’, 353 SEL/18/17, no folio.

[16] Archives départementales de la Seine-Maritime (Rouen), Série M: Administration générale at économie du département, Sous-série 4M (Police), 4M809 (hereafter Rouen 4M809), telegram dated 29 January 1886. I am grateful to Dr Regnard for her generous sharing of these vital primary sources. All translations from this source are mine.

[17] Archives départementales de la Seine-Maritime, 4M809, letter from the Préfecture du Département de la Seine-Inférieure dated 2 February 1886, 1. This reading of the damaged MS is supported by Céline Regnard, En transit: Les Syriens à Beyrouth, Marseille, Le Havre, New York, 1880-1914 (Paris: Anamosa, 2022), 160.

[18] I have failed to find an exact equivalent of this French transliteration. If this individual did indeed come from the mutasarrifate of Mount Lebanon, possible candidates for 'Birchalo' might include: Bshʿalah/Bcheale, in the Tannūrīn administrative district (mudīriyya), part of the larger canton (qaẓāʾ) of al-Batrūn; Bshallah (al-Mneitra/Kisrawān); or Bishlūn (al-ʿArqūb al-Janūb/al-Shūf): Fūʾād Efrām al-Bustānī (ed.), Lubnān: Mabāḥith ʿalamiyya wa ijtimāʿiyya [Lebanon: Scientific and Social Investigations] (2 vols., Beirut: Lebanese University Press, 1969 and 1970), i, 49–60, lists 1,141 villages in the Mount Lebanon mutasarrifate in alphabetical order.

[19] Almost certainly the Jubeil administrative district surrounding the ancient port city of Byblos and part of the larger canton of Kisrawān: Antoine A. Khair, Le Moutaçarrifat du Mont-Liban (Beirut: Lebanese University, 1973), 16–17.

[20] Again, an exact equivalent of this French transliteration has been impossible to find, either in Mount Lebanon or the mutasarrifate of Tripoli to the north.

[21] See Note 20, above.

[22] Rouen 4M809, letter from the Préfecture du Département de la Seine-Inférieure dated 2 February 1886, 1–2.

[23] Ibid., letter dated 16 February 1886.

[24] Ibid., telegram dated 20 February 1886.

[25] Ibid., letter dated 22 February 1886, 3.

[26] Ibid., 'Deportation', letter from the 2me Bureau of the General Security Directorate at the Interior Ministry, dated 27 February 1886.

[27] Ibid., letter from the Le Havre Police Commissariat, dated 5 March 1886; also letter from the Sous-Préfecture du Havre, dated 9 March. See also MMM, Microfilm 159, Shipping and Mercantile Gazette and Lloyd’s List, 8 March 1886, 6. The British Queen, owned by the Cunard line, sailed from Liverpool's Coburg Dock to the Levant and Constantinople from April 1851 until she was commandeered for service in Crimea in 1854. After the war, she was used for the trans-Atlantic crossing from Liverpool to New York via Halifax for a short time before becoming a regular fixture on the Liverpool-Le Havre run in 1863. She was finally sold for scrap in 1898: Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping: 1 April 1886–31 March 1887 (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1886), 510; see also University of Liverpool Library, Special Collections and Archives, D42/PR4/4/2. The Cunard Line was among the leading shipping companies involved in a vigorous competition for the lucrative migration market: Francis E. Hyde, Cunard and the North Atlantic 1840–1973: A History of Shipping and Financial Management (London: Macmillan, 1975), 58–89.

[28] Rouen 4M809, telegram dated 13 March. Shipping and Mercantile Gazette and Lloyd’s List, 13 March 1886, 5 and 6, confirms that the British Queen docked in Le Havre on 12 March, the day before the cited telegram.

[29] 'Destitute Syrians in Liverpool: Extraordinary Conduct of French Officials', Liverpool Daily Post, 26 March 1886, 5.

[30] LRO, microfilm of ‘Admission Register (25 January 1885–25 September 1886, A-K)’, 353 SEL/18/17, no folio.

[31] Ibid., microfilm of ‘Religious Creed Register (December 1883–May 1886, A-D)’, 353 SEL/19/37, no folio.

[32] Liverpool Daily Post, 26 March 1886, 4 and 5. Here the paper is directly quoting a letter sent by the Select Vestry to the LGB in London, see Note 38, below.

[33] Manchester Guardian, 26 March 1886, 5.

[34] New York Times, 12 April 1886, 4.

[35] Sheila Kelly, 'Select Vestry of Liverpool and the Administration of the Poor Law 1821-1871', University of Liverpool MA thesis, 1971.

[36] TNA, Kew, MH 12/5999, 30233/86, Hagger to LGB, 24 March 1886, 3–4. See also Liverpool Daily Post, 26 March 1886, 4 and 5. Henry Joseph Hagger (1829–1911) served as Vestry Clerk for nearly fifty years: https://hagger.one-name.net/henry%20joseph%20hagger.htm.

[37] TNA, Kew, MH 12/5999, 30233A/86, and 34014/86, Alfred D. Adrian, LGB, to Under-Secretary of State, Foreign Office (henceforth FO), with the subject 'Asiatic paupers', 26 March 1886; and T.V. Lister, FO to LGB, 5 April 1886, 2–4. An experienced diplomat and civil servants, Thomas Villiers Lister (1832–1902) was Assistant Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs for 21 years. Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, was a member of William Gladstone's Liberal government until its defeat in the general election of July 1886.

[38] William Henry Waddington (1826–94), the son of naturalized French citizens, was briefly Prime Minister of France in 1879 and served as French Ambassador to London from 1883 for 10 years.

[39] TNA, Kew, MH 12/5999, 30233/86, extract of letter from Waddington, French Embassy, to HO, enclosed in Nott-Bowen to HO, 30 March 1886, 2–3. Charles de Freycinet (1828–1923) served as Prime Minister for four separate terms.

[40] TNA, Kew, MH 12/5999, 30233/86, cover letter from Godfrey Lushington, Home Office (henceforth HO), to FO, 19 March 1886; cover letter from Edward Leigh Pemberton, HO, to LGB, enclosing the mayor’s letter and police report, 24 March 1886; cover letter from Radcliffe to Childers, 22 March 1886; letter from Captain J.N. Nott-Bowen, Head of the Liverpool Constabulary Force, including a report on the investigation into the eleven 'natives of Tripoli' by Detective Sub-Inspector d’Espinay, who had been 'informed by Mr Maguire Superintendent of the Relief Department at said Workhouse that the Parochial Authorities had never entertained the idea of sending them back to France', 30 March 1886, 5–6. Hugh Childers had served as Secretary of State for War and Chancellor of the Exchequer in previous Gladstone administrations but was Home Secretary for just over five months.

[41] TNA, Kew, MH 12/5999, 37167/86, Hagger to LGB, 15 April 1886, 1–3. This last observation is undermined by the travelers’ claim while in French detention to have been almost all single. See also LRO, Select Vestry, Workhouse Committee Minute Book (1 October 1885–20 June 1889), 353 SEL/10/12 (henceforth WCMB), 76. The letter was forward to the Foreign Office the following day by Cornelius Dalton, Assistant Secretary to the LGB: TNA, Kew, MH 12/5999, 37167/86, 1–2.

[42] Sir Julian, later 1st Baron Pauncefote (1828–1902) was Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs for seven years from 1882 before being sent to Washington, D.C., as Ambassador to the United States.

[43] Ambassador Rüstem Mariani, a Florentine Catholic, had been mutaṣarrif of Mount Lebanon for ten years from 1873 and was immediately thereafter posted to London. Several online sources erroneously give the date of his death as 1885.

[44] TNA, Kew, FO 78/3916 (no folios), Rosebery to Rustem, 21 April 1886. Copies of this letter and the subsequent reply from the ambassador, were forward to the LGB on 6 May 1886: ibid., MH 12/5999, 44048/86.

[45] Ibid., FO 78/3916m Rustem to Rosebery, 28 April 1886 (my translation from the French original).

[46] Mussabini had served as Ottoman Consul in the city since 27 March 1850: Edward Hertslet, ed., The Foreign Office List, Forming a Complete British Diplomatic and Consular Handbook … Together With a List of Foreign Diplomatic and Consular Representatives Resident Within the Queen’s Dominions: January, 1878 (London: Harrison, 1878), 303. See also P.L. Cottrell, 'Liverpool Shipowners, the Mediterranean, and the Transition from Sail to Steam During the Mid-Nineteenth Century', in From Wheel House to Counting House (ed. Lewis R. Fischer) (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1992), 201.

[47] Evening Express, 15 April 1886, 4. This article was based on the letter sent by Henry Hagger to the LGB the same day: see Note 41, above.

[48] LRO, Select Vestry, WCMB, 78 (22 April 1886) and 83 (13 May 1886). William Rathbone (1819–1902) was a Liverpool merchant and Liberal Party MP for Arfon, in north-west Wales, between 1885 and 1895. His involvement with the city’s workhouses, especially their hospital facilities, stemmed from his friendship with Florence Nightingale.

[49] TNA, Kew, MH 12/5999, 39763/86, 1–2, Hagger to LGB, 22 April 1886. The letter was only forwarded to the Foreign Office five days later: C. Boyle, Assistant Secretary to the LGB, to FO, 27 April 1886: ibid., 39763A/86.

[50] Liverpool Echo, 26 April 1886, 3.

[51] James Bryce was an extraordinarily talented politician. At the time of this correspondence, he was Liberal MP for South Aberdeen, a frequently published historian and, at the same time, Regius Professor of Civil Law at the University of Oxford, a position he had held since 1870: H.A.L. Fisher, James Bryce (2 vols., New York: Macmillan, 1927), i, 188–90.

[52] TNA, Kew, FO 78/3916, Bryce to Rustem, 21 May 1886.

[53] Ibid., Rustem to Bryce, 24 April 1886.

[54] LRO, Select Vestry, WCMB, 90.

[55] Saloni Mathur, 'Living Ethnological Exhibits: The Case of 1886', Cultural Anthropology 15/4 (2000), 492–524.

[56] Liverpool Daily Post, 11 June 1886, 2.

[57] '1886 Liverpool International Exhibition', FTL Design, History of Technology: https://1886le.ftldesign.com/ (accessed 2 November 2023).

[58] Liverpool Daily Post, 2 June 1886, 4. The exhibition had been opened by Queen Victoria on 11 May 1886.

[59] Liverpool Mercury, 22 May 1886, 6.

[60] Liverpool Daily Post, 14 May 1886, 4. During the summer, Rathbone sent his own list of the eleven men and their home addresses, via the Foreign Office, to Rustem Pasha. Unfortunately, the list (which might have corroborated or corrected the spellings of both the French list and the passenger manifest) has not survived with the draft of the cover letter transmitting it: TNA, Kew, FO 78/3916, Bryce to Rustem, 15 June 1886.

[61] 'Article Six' in Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1894 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894), 714.

[62] TNA, Kew, FO 78/3916, Bryce to Rustem, 5 July 1886.

[63] Ibid., Rustem to Bryce, 9 July 1886 (my translation from the French original). The ambassador had informed the Foreign Office of Mavrogordato’s nomination by the Sublime Porte on 7 May 1886 (ibid.) and the appointment was formally announced six weeks later: London Gazette, 18 June 1886, 2910.

[64] TNA, Kew, FO 78/3916, Rosebery to Rustem, 16 July 1886.

[65] Ibid., MH 12/5999, 66775/86, 1–2, Pauncefote to LGB, 16 July 1886.

[66] Liverpool Echo, 14 July 1886, 3.

[67] The election, which took place between 1 and 27 July 1886, was triggered by the defeat of Gladstone’s Government of Ireland Bill. Gladstone’s latest administration had only been in power since January.

[68] LRO, Select Vestry, WCMB, 105.

[69] Liverpool Mercury, 23 July 1886, 6.

[70] TNA, Kew, MH 12/5999, 69640/86, 2, Hagger to LGB, 28 July 1886.

[71] Ibid., MH 12/5999, 66775/96, internal LGB notes between 29 July and 2 August 1886.

[72] Ibid., FO 78/3916Bryce to Rustem, 4 August 1886.

[73] LRO, Select Vestry, WCMB, 110 (5 August 1886).

[74] 'Last of the Syrians', Evening Express, 5 August 1886, 3.

[75] TNA, Kew, MH 12/5999, 72767/86, Hagger to LGB, 7 August 1886. Unfortunately, the name of the vessel is illegible.

[76] Archives départementales de la Seine-Maritime, 4M809, telegram dated 15 March 1886.

[77] LRO, Select Vestry, WCMB, 115 (19 August 1886). This response had been relayed to the LGB by Pauncefote at the Foreign Office on 12 August 1886 and by the LGB to the Select Vestry on 16 August 1886: TNA, Kew, MH 12/5999, 73982/86 and 73982A/86.

[78] Ibid., FO 78/3916, Rustem to Iddesleigh, 9 August 1886 (my translation from the French original).