Community Archives, Archives of Community

It was the summer of 2016 when I received an email advertising a talk at Princeton on a recently discovered archive in the former patriarchate of the Syriac Orthodox Church. I was preparing to begin my doctoral studies at Yale University, where I was to write a dissertation on the history of the modern Middle East. Broadly interested in matters of religion, sectarianism, and minority difference but without a clear dissertation topic in mind, I was on the lookout for primary source collections that might constitute the empirical basis of a contribution to the field. The Syriac archive, located outside the southeastern Turkish city of Mardin, piqued my interest.

I wrote an email to George Kiraz, the speaker who had delivered the talk at Princeton. Kiraz, I would learn, was a deacon in the Syriac Orthodox Church as well as a scholar in his own right, having published widely on Syriac history, grammar, and linguistics. One of the central figures behind the renaissance of the academic field known as “Syriac Studies,” Kiraz had discovered the patriarchal archive in 2005 and returned with a team of researchers to digitize its contents, which comprised enough material to generate 19,000 separate images.[1] These materials consisted, for the most part, of letters and petitions from members of the Syriac Christian community in the Ottoman Empire—resident across an expansive geography stretching from Baghdad to Jerusalem, Aleppo to Diyarbakır—to the patriarch of the church in Mardin, home to the historic Syriac monastery Dayr al-Zaʿfaran. Generally penned in Garshuni, or Arabic written in the Syriac script, though frequently also written in traditional Arabic, Ottoman Turkish, Turkish Garshuni, or Syriac, the letters and petitions were notable both for the variety of voices represented therein—not merely clergymen and notables but even common villagers were among the letter writers—as well as for the diverse subjects to which they pertained: taxation, intercommunal conflict, famine, and so forth. The archive was a veritable treasure trove of historical evidence for manifold aspects of the social, cultural, economic, and religious history of the late Ottoman Empire.

The monastery Dayr al-Zaʿfaran in Mardin. Photo taken by the author.

When we met that summer at Beth Mardutho, a center for Syriac Studies that Kiraz had established in Piscataway, NJ, he encouraged me to consider working on the archive as part of my dissertation research, even offering to set up a meeting between me and the patriarch of the church to ask permission to do so. I agreed, and several months later the patriarch, with whom I met in Paramus, NJ while the ecclesiastical leader was in transit to an ordination in Detroit, gave me permission to begin research on the digital archive. The only condition was that I work with Kiraz to catalogue its contents. I began studying Syriac and Garshuni in order to be able to access the material and quickly dove into my research.

Initially thrilled merely to have access to this nearly untapped repository of information on late-Ottoman history, I soon began to wonder about the history of the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchal Archive itself. I had noticed that the majority of the letters and petitions held in the archive dated to a particular period between, roughly, the early 1870s and the mid 1890s, appearing to indicate an increase in correspondence between the Syriac patriarch and the wider Syriac community in these years. What is more, the contents of the documents appeared to suggest that there was something novel about the degree of correspondence taking place between the patriarch and the community in this period—that it was not mere historical accident that so much documentation existed from these two decades but rather was indicative of a shift in the organization of the Syriac community itself.

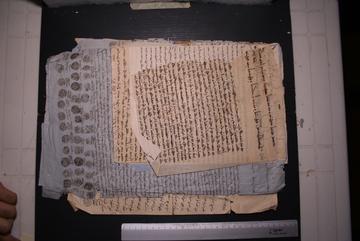

The archive as it was found in Dayr al-Zaʿfaran in 2005.

Photos courtesy of George Kiraz.

What I came to see was that the existence of the Syriac Patriarchal Archive, more than merely yielding a remarkable cache of historical information, attested to a major historical transformation among the Syriac Christians in the final decades of the nineteenth century. That transformation involved the central Syriac church inserting itself much more intensely than had been the case before into the many different communities of the sprawling Syriac Christian world of the Ottoman Empire. Prior to this period of communal reorganization and reform, the Syriac Christians of the Ottoman Empire, I realized—particularly those resident in the mountainous region of great Syriac settlement known as Tur Abdin—had lived in decentralized networks of tribal and congregational affiliation often with little or no oversight from the central Syriac church under the leadership of the patriarchate at Dayr al-Zaʿfaran. Priests were appointed locally, ritual practices differed from village to village, and hierarchies of ecclesiastical authority were varied. There existed little sense among the Syriac Christians that they comprised constituent units of a broader community of “Syriac Christians,” even if they were united, for the most part, by a common Syriac liturgical tradition.

What the Syriac patriarchal archive held was thus not the records of an already-existing communal network but rather the documents of a community in the making, or at least, a certain instantiation of community that was particular to this era. That this was the case was evidenced by the archive’s contents, which revealed not a Syriac community already fully formed but a central church and ecclesiastical network coming into contact with communities that, even if they were somehow recognizably Syriac Christian, were nevertheless unfamiliar, often having maintained little contact with the central church for generations. Some of these communities had been without Syriac priests for a hundred years; some were without a single individual who could read the Syriac language; some spoke only Armenian and went to Armenian priests for spiritual services and the sacraments.

Having realized the context in which this archive had come into being, my historical approach to it appeared to require modification. Rather than what information this archive could reveal of the history of the Syriac Christians and of religion and community in the late Ottoman Empire, the most pertinent and pressing question seemed to be a different one, namely: what was this the archive of? What was behind the process of communal reorganization—the church’s heightening presence in Syriac lives across the Ottoman Empire—that had generated this explosion of documentation? Should this archive be understood as constituting an archive of Syriac Christian communal history? Or was this the archive of a community coming into being?

Batch of letters from the archive. Photo courtesy of George Kiraz.

Answering these questions required not only that I change my approach to the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchal Archive, but also that I call into question some of the terms of my inquiry, most significantly, that of “Syriac Christian” itself (Arabic: Suryani; Turkish: Süryani). At the outset of my research on the Syriac archive, I had conceived of my project as an investigation into a particular religious community as they navigated the changes of the Ottoman nineteenth century: the Tanzimat reforms and the concomitant rise of the ideals of equality and religious freedom; the influx into the eastern Ottoman provinces of Protestant missionaries armed with new ideas about religion, history, and culture; the rise of a modern regime of property rights. Yet I came to see that the term I was using to identify this community (Suryani/Syriac Christian) was itself a term of great contest among those I had identified as connected to it. If certain figures represented within the archive—the patriarch, for instance, or local notables in Tur Abdin—were concerned to identify the broader community of which they saw themselves to be part as collectively “Syriac Christian,” there were manifold others that evinced a distinct ambivalence about this communal designation, preferring to conceive of themselves as members of diverse tribes (ʿashirah), congregations (jamaʿa), or villages (qaryah) instead. On display in the archive, in other words, was less a communal history than a history of a process of contested communal formation.

The challenge for the historian as I see it is to place this contest over community in its proper historical context—to ascertain why the category “Syriac Christian” became a contested one in this period, why certain individuals were determined to identify themselves, in addition to (those they saw as) their communal brethren, as Syriac Christians while others rejected this designation, and what the consequences of this politics of identification were for those affected by it. Answering these questions necessitates a much broader sort of inquiry, one that extends beyond the context of the Syriac archive and that brings into view the broader imperial changes of which the archive was a part. Enlarging the scope of the project in this way, I have come to see that the contest over naming and identification made apparent in the Syriac archive was not particular to the Syriac Christians but rather was intimately connected to a new regime of imperial administration that was taking hold across the late Ottoman Empire more generally, reshaping forms of communal relationality and self-understanding across diverse regions and populations.

I have further come to understand that this new system of nineteenth-century state administration had something to do with a concept that I seemed to continually encounter in archival documents from the period: “millet.” This term was equally as contested among the Syriac Christians as was the term “Syriac Christian” itself, and in fact both these terms paired to form a new concept closely associated with the emergent communal formation that my work has been investigating: Süryani milleti, or millat al-Suryan, the Syriac Christian millet. My dissertation, “The Syriac Christians of the Late Ottoman Empire: Secularism, History, and the Struggle for Millet Recognition,” connected this new communal formation to what I came to see was a broader nineteenth-century politics of Ottoman millet recognition—a system that was highly consequential not merely for the Syriac Christians but for diverse communities across the Ottoman Empire. In the book project that this dissertation will become, tentatively titled Ottoman Secularism: History and Difference in the Nineteenth Century, I work to understand how this system of millet recognition was an essentially secular system that broke in important ways from the Islamically grounded tradition of imperial rule that preceded it. The Syriac Orthodox Patriarchal Archive of Mardin, I wish to suggest, is a key archival location from which to understand this sweeping transformation that fundamentally re-ordered the late-Ottoman world.

[1] Khaled Dinno, “The Deir al-Zafaran and Mardin Garshuni Archives,” Hugoye.